Mike was one character that still looms large in my memories of my early fisheries career. Mike was an enigma in many ways. Originally, he had studied business and began his career as a commercial loans banker, and he was good at it.

A life-long learner, who loved to explore and understand the world around him, Mike had a passion for all things wild. One day he simply walked out the bank door to a life of freedom and uncertainty. Their loss was our gain.

It was the summer of 1981, Mike was the captain of the jet boat, and I was the crew, as it powered up the Zymoetz River, heading up into the mouth of the lower canyon. Also known as the Copper River, it is a big, powerful, glacial- coloured tributary of the Skeena River, near the town of Terrace, in northern B.C. It was 32 degrees Celsius in Terrace that week. Mike was tall, bare- chested, wearing cut off shorts and sun-tanned as “brown as a berry” as my English mum used to say.

Newly assigned as the SEP support biologist for Skeena River and northern B.C. Community projects, I was here to participate, observe and learn about the enhancement efforts in the watershed. I helped set the gill nets, jumped into the water to haul them to shore, and captured entangled Chinook to put into the holding pens. It was hard physical work but Mike made it look so easy, and I never saw the smile on his face waver for a minute that day. He was in his element.

Mike was a local resident of Terrace, a passionate angler obviously skilled at operating a jet boat. Bob Brown, the DFO senior technician responsible for implementing the Zymoetz River field program, had hired Mike on a short-term contract to help with the broodstock collection effort.

Bob knew how to run a field program and he knew how to measure up the crew he hired. He started his career with the military in the far north and talked about shooing polar bears away while heading for the privy and working on the DEW line in the Canadian high Arctic.

He migrated south to join DFO and was assigned to some of the remotest parts of the west where salmon live. Bob had been around and knew DFO operations inside and out; he picked Mike, and that said a lot.

The Zymoetz River program captured adult Chinook in the lower river, held them until maturity, collected the ripe salmon eggs and then fertilized, incubated and reared the resulting juveniles at a site in the upper Zymoetz River.

(As big as my sister)

The tagged and marked Chinook salmon juveniles were then released into the river in late spring to begin their journey to the ocean. It was an effort to stop the decline of the Zymoetz River Chinook population and also opened an opportunity to fin mark and tag the hatchery juveniles. When marked adult Chinook are harvested in ocean and river fisheries, the heads are removed and this small wire tag recovered.

Each tag has a unique code etched on its surface that indicates where the salmon were released from, in this case the Zymoetz River, 1981. This provides critical information on when and where salmon are caught and marine survival and fishery exploitation rates, all important information for proper management of the species.

This was a big deal at the time. Not just because Chinook salmon runs in the northern BC had been declining over past decades. DFO managers also knew they had an even bigger problem coming down the pipe.

Canada and the U.S. had begun negotiations in the mid 1970’s on a then ground-breaking “Pacific Salmon Treaty” which would be ultimately signed by Prime Minister Mulroney and President Reagan in March 1985. Some of the key points of agreement between the two countries were: each country should strive to reduce interceptions of salmon not produced by that country; each country should be given credit for any salmon unavoidably intercepted in the other countries fisheries, and the final division of total catch should fairly represent the production coming from each of the respective jurisdictions.

The big problem was that Canada had very little data on where northern BC Chinook went in the ocean and suspected they went far north into Alaska fisheries. The U.S. wanted hard data; without it they would not give any credit for taking “their” not “our” Chinook in Alaskan waters.

The Chinook Mike caught all that summer for the Zymoetz River enhancement program, and salmon he caught in later years for the important enhancement and coded wire tagging program on the Kalum River, played a key role in Canada efforts to monitor, mark and track lower Skeena River Chinook to inform domestic and international fisheries management.

Dave Elkins wrestling a Kalum River Chinook

Mike continued to play his part over the next thirty years, helping Canada deliver a more sustainable management regime for Pacific salmon in the North Coast of B.C.

Over the years, I came to know Mike much better and on one trip north, met his dad, Jack, over dinner at their place. Jack, also known as “Pops” liked to cook “for the boys” when they were in town.

When we arrived, he showed us this rickety aluminum tee pee looking contraption that was spewing out big clouds of smoke. He told us he had been smoking some steaks for over four hours to serve us for dinner. We were a tad worried that dinner would consist of well done beef jerky. But alas, we couldn't be more wrong! He removed them from the smoker, threw them on the BBQ and served up perfectly cooked medium rare, tender juicy steaks. Dinner was topped off with a wicked spicy hot delicious Caesar salad. Jack sat at the head of the table and said very little except that he liked his salad spicy.

Jack had followed Mike to the Coast from Edmonton, Alberta, to finish his career, and on retirement went to live with him. He was a generous and kind soul and had passed this family trait on to his son Mike. Jack was not much of a talker but did like to keep busy. Jack was like a lot of Prairie folk I’ve met. They take pride in being self-sufficient and can just about fix or build anything.

Mike casually mentioned that Jack had been up to the upper Zymoetz River field camp the week before and had done some improvements to help the seasonal workers hired to fin clip and coded wire tag the Chinook juveniles.

Ron Tetreau and Gord Wadley, the cowboy-hatted duo then working for the BC Ministry of Fisheries had also been up at the camp with Jack that week, to check out what was going on with the steelhead spawning at the nearby outlet of McDonell Lake. Together they had helped out the crew to make the camp a little more hospitable. We were heading there the next day.

When we arrived, it was apparent the tagging crew was entirely female. The bias of the day was that women, with smaller hands, could handle the little fish much faster than men; sexism in action, circa 1983. The crew was led by Thyra Nichols, a no-nonsense woman, with a wicked sense of humour, out of the bucolic town of Ladysmith on Vancouver Island. Thyra organized most of the coded wire tagging in the more remote sites that SEP community programs operated at that time.

Thyra made up the crews, she picked all women, and nobody I know was going to question her judgment, or at least lived to tell about it. She was so rough and tough, with such a soft fuzzy warm heart, my wife and I later named our only daughter after her. So that when she grew up she could go forth and conquer the world just like her namesake. Thyra is the feminine form of the Scandinavian god of war (Thor), just saying.

When we arrived, Thyra came out of the tagging tent and met us at the truck. We gave the crew a wave, but they were busy clipping, tagging and moving the small Chinook salmon. We did not want to disturb them and would leave introductions to when they had their next break. We sat down in the truck to go over the tagging plan with her and discuss any technical or logistical issues that needed to be resolved.

At one point I had to excuse myself to ask for directions to the camp “facilities”. “Just go around the corner, on the other side of the big Spruce tree. Jack was up here last week and fixed it up for us” she said with a big smile. Being a temporary field camp, I wasn’t expecting much.

Perhaps a rickety shack thrown up in a hurry, made from random pieces of wood salvaged from some construction project, precariously propped up over hastily dug hole. The “palace”, probably located in some patch of prickly wild rose bushes, would be about par for the course.

When I rounded the tree, there stood the most carefully crafted outhouse I have ever seen in a field situation. This was no last minute, happenstance construct. This was a real beauty. As I stepped closer heading for the lovely abode I noticed something peculiar. I could not find the door. I could find the opening to the outhouse but no door. This was a little awkward but I figured I would just hurry up and get on with it and all would be well.

As I sat there I realized Jack’s genius. It was a quiet, peaceful throne where one could gather one’s thoughts on the meaning of life. The little house was open to the air, with a slight Spruce scented breeze wafting between my knees. The outhouse was positioned, obviously by plan, in the direction of a spectacular snow-capped crag in the distance. What a guy.

Just about now there was the soft sound of conversation coming closer. It got louder quickly. More boisterous, more immediate, many voices, here, now!

Thyra thought it was time I met the crew.

Khutzeymatten Grizzly (Photo Courtesy BC Parks)

When not working, Mike was fishing. When he was fishing, he was either float fishing for Chinook salmon in the Kalum River, throwing a spoon to coho salmon on the Gitnadoix River, rolling a fly with his double handed Spey rod for summer steelhead in the Copper River, or mooching a herring for winter Chinook in the tidal rips of the Work Channel in Prince Rupert. Mike did not stay indoors much.

When he wasn’t working or fishing, he was hunting bears. He was obsessed when armed - with his camera. White, black, or brown, Mike seemed to have an understanding with bears. The Black Bears, to him, were the neighbor, you always chatted with them as you both did your daily tasks. The North Coast Spirit (white) bears were acquaintances that appeared in your life, once in a while. But the coastal Grizzly (brown) bears were dear old friends that marked the passage of your life.

Each spring Mike would fuel up his jet boat and go down to the coast for an extended trip into some remote river estuary. There he would set up his camera and sit for days in the meadows. He would wait to meet the Grizzlies who also came down to the sea to eat the new sedges and grasses after their long winter sleep. Bears have poor eyesight so if they came too close he would start to talk to them in his low, gentle voice.

Usually once they saw him they would put their head back down and keep feeding. If they still seemed uncomfortable, Mike would lean over and grab a handful of grass and place it in his mouth. He was just letting them know he was there for the same reason as they were. Everyone would be just fine; they understood.

For almost thirty years Mike was hired on a seasonal contract by DFO to provide technical support for SEP community salmon enhancement facilities in the lower Skeena River and the coastal areas from Portland Canal, at the Alaska border south down to Douglas Channel. One of the community hatcheries he provided technical support to was located at Hartley Bay (Txalgiu) part of the Gitga’at First Nation. Reached only by boat or air, the majority of visitors to this remote village arrive by float plane from Prince Rupert. Not Mike.

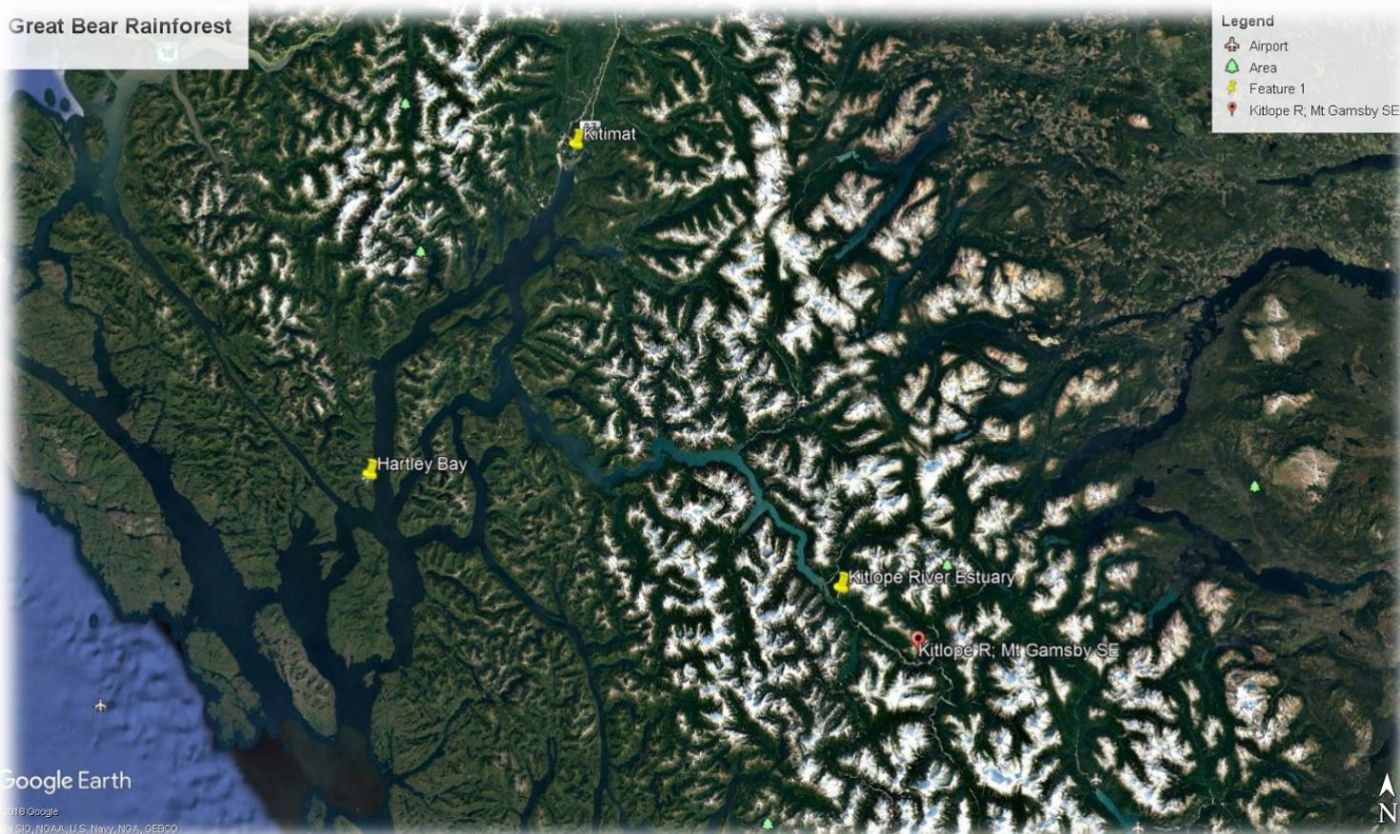

As part of his SEP job duties, Mike was required to make regular trips into Hartley Bay to provide support to the salmon programs at the village. He would often launch his jet boat at Kitimat and travel west out to Hartley Bay, at the mouth of the Douglas Channel. This was a 90 km trip one way. This meandering coastal fjord was known to be a windy place. Inflow winds and outflow winds and everywhere flow winds made travel along the channel challenging with rough seas pretty well expected. This was just the way Mike liked it, kept down the crowds.

When Mike’s work was done with his old friends at Hartley Bay, he would book off the clock, refuel and head back east up the Douglas Channel. It just so happened that one of Mike’s favorite watersheds to photograph bears was in the remote Kitlope River, deep into what is now the “Great Bear Rainforest”. On his way back to Kitimat, he would often hang a right at a familiar coastal fjord, and head south another 90 km’s towards the estuary of the Kitlope River. As was his habit, Mike was off to see what other “old friends” might be at home.

Mike was the type of guy that nothing seemed to bother him much. In a tight situation he would always say something positive, in a low, calm voice and finish the sentence with the arch-typical Canadian, eh? But in Mike’s case it was more a long drawn out sigh. A typical Mike comment would be “Well it could be worse, the tire is flat, we are about 30 km from town here in the bush, and it’s starting to snow but I do have some sandwiches from yesterday’s lunch in the truck, “eeehhhhhhhhhhh!”

In all my years of knowing Mike I only saw him get mad once. A small group of us were on the bank of Kalum River near the Kitsumkalum Indian Band Office, in Terrace BC. We had just come from a meeting with the Band Manager, Steve Roberts, at the band office. We were doing some enhancement planning for the salmon facility the First Nations operated up the river. We had come down to the river to take a break, get some fresh air and enjoy the bright fall day.

Some guy that seemed to sort of know Mike (everyone seemed to know Mike), had pulled up in his truck and just seemed ready to whine. He started complaining about the there being no fish to catch, too many other anglers, DFO regulations – a familiar litany - and that was just in the time he was sliding out of his truck to face our group. I figured it best to let Mike do the talking since I was from that bad place called Vancouver and worked for DFO. I would rather be walking a river counting salmon in a snowstorm than argue with this person with this attitude I did not share.

Mike just listened in his usual serene way until the complainer made a fatal error; he started to talk in an uncomplimentary way about “those Indians”. Mike always treated everyone he worked with or knew with the respect and dignity each of us deserves. He judged people on their character not on their physical appearance or cultural or ethnic background.

To hear an ill-informed rant about his colleagues and friends was more than the usually easy-going Mike was prepared to stomach. Mike had always been made welcome in the First Nations villages along the Skeena River and the North Coast. They welcomed him into their homes and families, because of who he was not what he was.

The misguided orator was just working up a good stiff breeze when I caught a look at Mike out of the corner of my eye and it was not a pretty sight. Mike was big, around 260 pounds, by my reckoning. He usually stood six-foot-tall, but he appeared to have grown a couple of more inches in the past minute or so.

What some would have called an ample belly seemed to have migrated upward and might be now called a barrel chest. His eyes were always a little buggy and somewhat bloodshot, but one of them was distinctly thinking about blowing out of its orbit. Instead of his usual lightly flushed face, I would have definitely have categorized it in the red spectrum.

When a Grizzly bear get agitated they sort of purse their lips and give out a “huufff” sound. Mike spent way too much time hanging out with Grizzly bears in my opinion as I think I heard a similar sound coming out of Mike. He always seemed to understand bear talk quite well.

It appeared around this time Mr. Complainer had also noticed a change in Mike’s demeanor. He got quiet rather quickly. He must have known Mike well enough to sense what was now facing him, with a slight lean in his direction, was out of character and he best make himself scarce.

Being not as polite and cultured as Mike, and growing up in Surrey B.C., where we do speak a different regional form of English, the only way I could describe his departure, was he (expletive deleted) off in a big, big hurry. All I heard Mike say as this bright light left the scene was, “I don’t like that guy.”

Mike and Lynn going to visit “old friends” down the Channel

Mike continued throughout the years to provide his thoughtful and supportive advice to the SEP community hatcheries at Kincolith, Deep Creek, Kitsumkalum (Site 11), Oona River, Oldfield Creek, and Hartley Bay. DFO, Community Advisor Barry Peters was his boss, partner and friend over most of those years and they were quite a team keeping the North Coast Community projects, happy, well run and doing the good work.

Mike was one of those people who could always be called upon to lend a hand, in winter or summer, in heat or snow storm, morning or night. Mike represented the solid rock that kept the SEP Community Programs on the straight and narrow. If old friends, Jim Culp or Grant Hazelwood from the Terrace Salmonid Enhancement Society needed a little muscle or brain power on a project of theirs, Mike would always answer the call

His beautiful wife Lynn never complained when Mike would get an urgent call for help. These might be as varied as: an egg incubator pipe had frozen, a storm had plugged the hatchery river intake, the fish were sick, or maybe the hatchery guard dog had just died and someone needed some consoling. He would drop what he was doing, pack up and head for the door. She knew the man she loved would not be that man, unless he was giving back to the people and wild things that he loved.

Later in life, Rob Dams, the new North Coast Community Advisor, who Mike liked to call “the kid” to his own great amusement, formed a close relationship that endured to the final day of Mike’s passing. Rare people like Mike don’t come along often, and no one knew that better than Rob.

Mike Whelpley is gone now. To my mind Mike represented the essential Canadian spirit: free to wander, free to dream and free to remake his life in the likeness of his own choosing. Mike freely chose to help salmon.

He was a Prairie boy, who had followed the setting sun, until he was captured by the salmon out on the rough edge of Canada. The salmon led him to rivers, mountain headwaters, estuaries and coast fjords. Salmon led him to Grizzly, Black and Spirit bears, and to remote First Nation villages, who had not forgotten their own stories. The salmon led him to friends and colleagues that won’t soon forget him.

ADDRESS

Oweekeno Village

CONTACTS

Email: brydonp@pwhatchery.org

Phone: (604) 449-2040